Technologists and policymakers largely inhabit two separate worlds. It's an old problem, one that the British scientist CP Snow identified in a 1959 essay entitled The Two Cultures. He called them sciences and humanities, and pointed to the split as a major hindrance to solving the world's problems. The essay was influential -- but 60 years later, nothing has changed.

When Snow was writing, the two cultures theory was largely an interesting societal observation. Today, it's a crisis. Technology is now deeply intertwined with policy. We're building complex socio-technical systems at all levels of our society. Software constrains behavior with an efficiency that no law can match. It's all changing fast; technology is literally creating the world we all live in, and policymakers can't keep up. Getting it wrong has become increasingly catastrophic. Surviving the future depends in bringing technologists and policymakers together.

Consider artificial intelligence (AI). This technology has the potential to augment human decision-making, eventually replacing notoriously subjective human processes with something fairer, more consistent, faster and more scalable. But it also has the potential to entrench bias and codify inequity, and to act in ways that are unexplainable and undesirable. It can be hacked in new ways, giving attackers from criminals and nation states new capabilities to disrupt and harm. How do we avoid the pitfalls of AI while benefiting from its promise? Or, more specifically, where and how should government step in and regulate what is largely a market-driven industry? The answer requires a deep understanding of both the policy tools available to modern society and the technologies of AI.

But AI is just one of many technological areas that needs policy oversight. We also need to tackle the increasingly critical cybersecurity vulnerabilities in our infrastructure. We need to understand both the role of social media platforms in disseminating politically divisive content, and what technology can and cannot to do mitigate its harm. We need policy around the rapidly advancing technologies of bioengineering, such as genome editing and synthetic biology, lest advances cause problems for our species and planet. We're barely keeping up with regulations on food and water safety -- let alone energy policy and climate change. Robotics will soon be a common consumer technology, and we are not ready for it at all.

Addressing these issues will require policymakers and technologists to work together from the ground up. We need to create an environment where technologists get involved in public policy - where there is a viable career path for what has come to be called "public-interest technologists."

The concept isn't new, even if the phrase is. There are already professionals who straddle the worlds of technology and policy. They come from the social sciences and from computer science. They work in data science, or tech policy, or public-focused computer science. They worked in Bush and Obama's White House, or in academia and NGOs. The problem is that there are too few of them; they are all exceptions and they are all exceptional. We need to find them, support them, and scale up whatever the process is that creates them.

There are two aspects to creating a scalable career path for public-interest technologists, and you can think of them as the problems of supply and demand. In the long term, supply will almost certainly be the bigger problem. There simply aren't enough technologists who want to get involved in public policy. This will only become more critical as technology further permeates our society. We can't begin to calculate the number of them that our society will need in the coming years and decades.

Fixing this supply problem requires changes in educational curricula, from childhood through college and beyond. Science and technology programs need to include mandatory courses in ethics, social science, policy and human-centered design. We need joint degree programs to provide even more integrated curricula. We need ways to involve people from a variety of backgrounds and capabilities. We need to foster opportunities for public-interest tech work on the side, as part of their more traditional jobs, or for a few years during their more conventional careers during designed sabbaticals or fellowships. Public service needs to be part of an academic career. We need to create, nurture and compensate people who aren't entirely technologists or policymakers, but instead an amalgamation of the two. Public-interest technology needs to be a respected career choice, even if it will never pay what a technologist can make at a tech firm.

But while the supply side is the harder problem, the demand side is the more immediate problem. Right now, there aren't enough places to go for scientists or technologists who want to do public policy work, and the ones that exist tend to be underfunded and in environments where technologists are unappreciated. There aren't enough positions on legislative staffs, in government agencies, at NGOs or in the press. There aren't enough teaching positions and fellowships at colleges and universities. There aren't enough policy-focused technological projects. In short, not enough policymakers realize that they need scientists and technologists -- preferably those with some policy training -- as part of their teams.

To make effective tech policy, policymakers need to better understand technology. For some reason, ignorance about technology isn't seen as a deficiency among our elected officials, and this is a problem. It is no longer okay to not understand how the internet, machine learning -- or any other core technologies -- work.

This doesn't mean policymakers need to become tech experts. We have long expected our elected officials to regulate highly specialized areas of which they have little understanding. It's been manageable because those elected officials have people on their staff who do understand those areas, or because they trust other elected officials who do. Policymakers need to realize that they need technologists on their policy teams, and to accept well-established scientific findings as fact. It is also no longer okay to discount technological expertise merely because it contradicts your political biases.

The evolution of public health policy serves as an instructive model. Health policy is a field that includes both policy experts who know a lot about the science and keep abreast of health research, and biologists and medical researchers who work closely with policymakers. Health policy is often a specialization at policy schools. We live in a world where the importance of vaccines is widely accepted and well-understood by policymakers, and is written into policy. Our policies on global pandemics are informed by medical experts. This serves society well, but it wasn't always this way. Health policy was not always part of public policy. People lived through a lot of terrible health crises before policymakers figured out how to actually talk and listen to medical experts. Today we are facing a similar situation with technology.

Another parallel is public-interest law. Lawyers work in all parts of government and in many non-governmental organizations, crafting policy or just lawyering in the public interest. Every attorney at a major law firm is expected to devote some time to public-interest cases; it's considered part of a well-rounded career. No law firm looks askance at an attorney who takes two years out of his career to work in a public-interest capacity. A tech career needs to look more like that.

In his book Future Politics, Jamie Susskind writes: "Politics in the twentieth century was dominated by a central question: how much of our collective life should be determined by the state, and what should be left to the market and civil society? For the generation now approaching political maturity, the debate will be different: to what extent should our lives be directed and controlled by powerful digital systems -- and on what terms?"

I teach cybersecurity policy at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. Because that question is fundamentally one of economics -- and because my institution is a product of both the 20th century and that question -- its faculty is largely staffed by economists. But because today's question is a different one, the institution is now hiring policy-focused technologists like me.

If we're honest with ourselves, it was never okay for technology to be separate from policy. But today, amid what we're starting to call the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the separation is much more dangerous. We need policymakers to recognize this danger, and to welcome a new generation of technologists from every persuasion to help solve the socio-technical policy problems of the 21st century. We need to create ways to speak tech to power -- and power needs to open the door and let technologists in.

This essay previously appeared on the World Economic Forum blog.

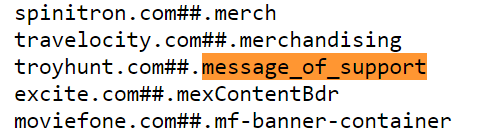

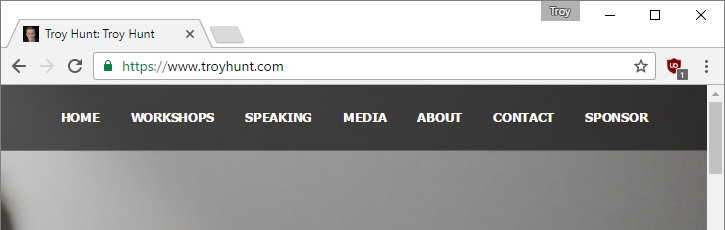

Meet the IBM z13 mainframe (source: IBM)

Meet the IBM z13 mainframe (source: IBM)

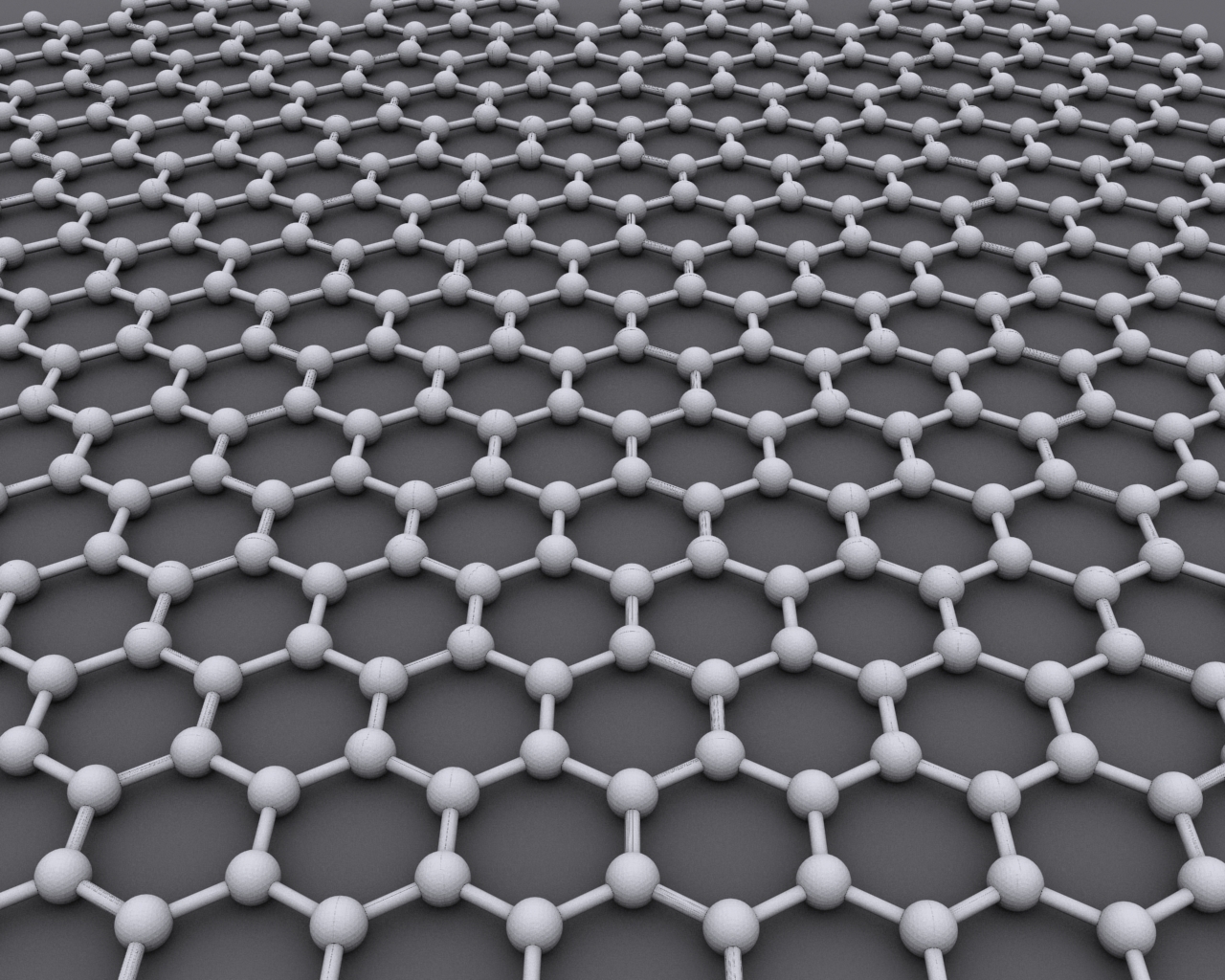

Graphene: a simple architecture that’s 100 times stronger than the best steel (credit:

Graphene: a simple architecture that’s 100 times stronger than the best steel (credit: